The seeds of a new world

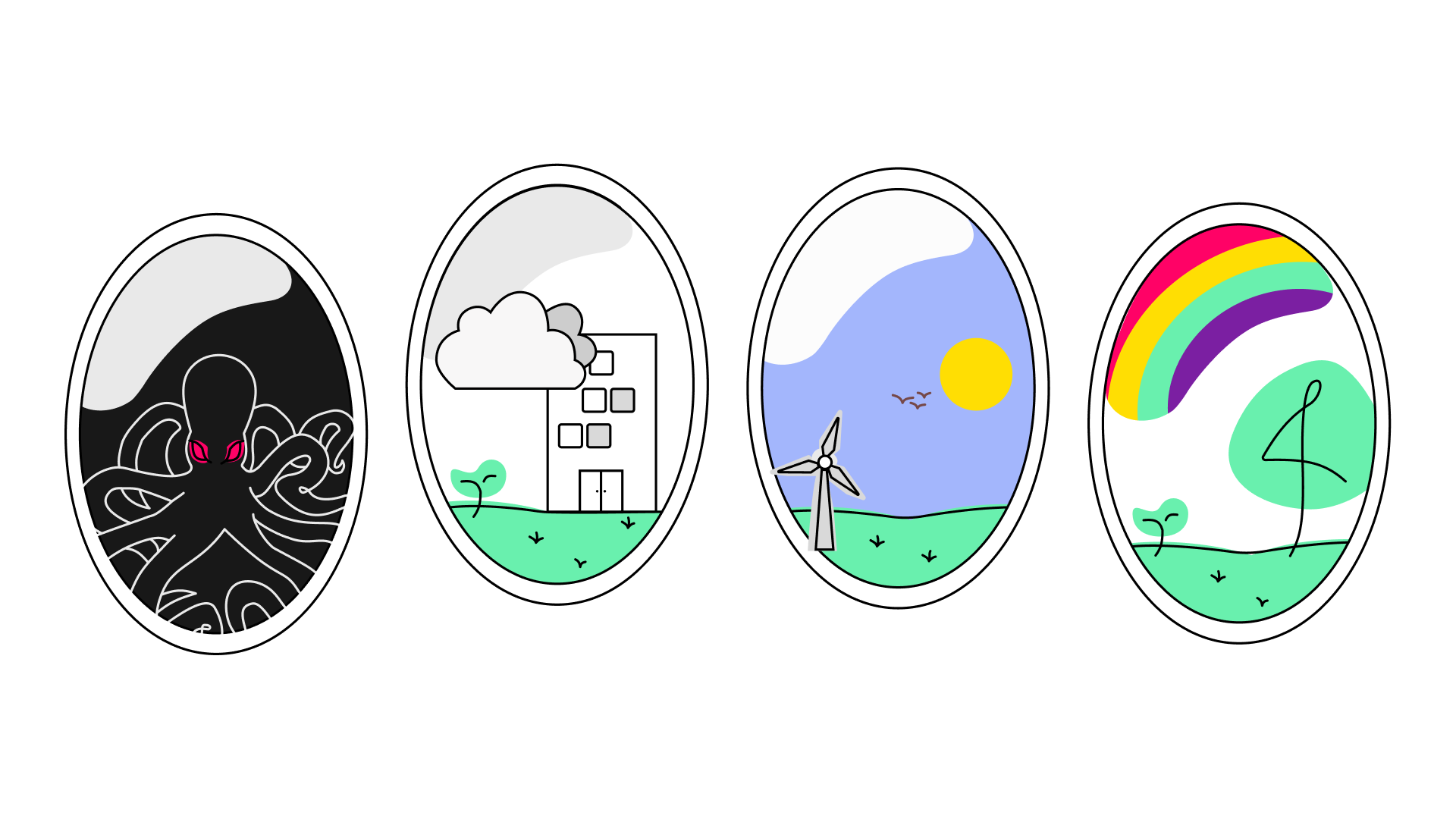

The sun is setting, and the birds outside are composing their final symphony for the day. A young girl named Alice is aimlessly wandering through her grandfather’s eclectic library. Amidst a labyrinth of dusty books and fading ink, her fingers brushed against a time-worn volume titled “The Wisdom of Wilderland.” It was a book on nature’s patterns, mythologies of indigenous peoples and biomimicry, a field she’d never heard of before, but as she read, her eyes widened in awe. She learned about the incredible mycelial networks that exist in many forests and gardens, a subterranean fungal internet that connects trees and plants, sharing resources and warning of dangers. She learned of the Dreaming of the Aboriginal peoples in Australia and their creation stories of the Rainbow Serpent. Alice’s heart swelled with hope. Earlier, her grandfather was sitting with her in the library, talking to her about so many of these big human problems. Many of which at the time seemed rather silly to her. That adults had created them and didn’t know how to solve them. While reading Wisdom of Wilderland she thought…”If the natural world can create such wonders, and ancient cultures have such wisdom, can’t we if we are part of it?”.

This post is inspired by a poem I wrote a couple of years back reflecting on our collective story and a sense of existential hope I cultivate in my life and with the Tethix team. (You can read the poem here)

Breaking chains and creating new games

Our modern landscape is a twisted web of physical and digital domains, each fraught with its own set of dichotomies, biases, and barriers. Yet as my poem suggests, we’re not hopelessly entangled; we’re faced with a vast, intricate gameboard. It beckons for our imaginative ingenuity to rewrite the rules, and to redefine the game itself.

Internally, we wrestle with our cognitive biases. Leon Festinger’s cognitive dissonance theory and the “backfire effect” underscore how unsettling truths can make us double down on our errors. These biases aren’t just personal stumbling blocks; they’re the building blocks for the systemic mazes we find ourselves in. Kimberlé Crenshaw’s intersectionality expands on this, reminding us that societal structures burden some more than others. The injustices many people in the world face are in large part a result of the patterns we keep reinforcing. So it’s not enough to break our individual chains; we must recognise the unique tangles of chains that others bear.

Breaking these free from these chains and forging ahead on a path to new games requires us to also reflect on how interwoven our myths, memes and stories are in how we see, act and exist in the world. How they are entwined in the technologies we create and use, and the social systems we inhabit.

Polarisation and cognitive biases

The modern landscape of digital interaction is a veritable petri dish for cognitive biases, aided and abetted by the algorithms that power our social media platforms and search engines. Far from neutral conduits of information, these algorithms are imprinted with our societal biases because they’re trained on data that contains them. This is a phenomenon not just documented in computer science, but one rooted in an expansive body of social sciences research.

Concepts like confirmation bias and groupthink help us understand the psychological mechanisms behind our behaviour. But when these ingrained tendencies meet the hyper-personalisation algorithms designed primarily to capture our attention and optimise for business outcomes and engagement metrics, the result is a cocktail of increasingly segregated ideological echo chambers.

Legal scholar Cass Sunstein grapples with this in his seminal work, “#Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media.” The docudrama ‘The Social Dilemma’ also delves into much of this, aspects of which I covered in commentary on the film in my November 2020 article.

But these platforms, ostensibly designed to connect us, have instead become fuel that amplifies our divides.

This isn’t just an issue of technology but a manifestation of its intricate interplay with human psychology and sociology. The algorithms, in essence, become a mirror reflecting our most segmented selves – only it’s a mirror that reflects back, confirming and deepening our pre-existing beliefs and biases. Addressing this is not just a matter of tweaking code but involves a broader, systemic approach that must take into account the complex socio-technical tapestry we’re part of. Some of it seemingly rigged that makes it hard to change.

Sustainable systems over rigged institutions

If you dig into the soil of our current socio-economic paradigm, like Alice would, you’d unearth layers of assumptions, some of which are disturbingly skewed. It’s a system structured to syphon wealth and resources upward, leading to billions of people in conditions of precarity and neglect. The trickle down story is apt. Most get but just a trickle while the torrent flows to those hoarding and buttressing their moats. Not only is this all just deeply inequitable, it’s ecologically unsustainable. Pushing a narrative and trajectory that defies the laws of thermodynamic and ethics alike. The shocking disparities in wealth and well-being aren’t just “how things are”; they’re the consequences of specific design choices in our social institutions grounded in a flawed worldview.

Enter alternative models like Doughnut Economics, conceived by Kate Raworth. This model challenges the ‘grow or die’ philosophy that has held such sway in economic thought. Instead of a linear, extractive model that treats the planet as an infinite resource and dumping ground, the Doughnut Economics model promotes circularity. This is fundamentally different to how we’ve been doing it. It evokes a picture of an economy where waste becomes input, where the concept of ‘trash’ is replaced by ‘nutrients for the next cycle’, aligning more closely with how natural ecosystems function. It is also about redefining prosperity, moving beyond GDP and material wealth to “less wrong” indicators that encompass social well-being, equity, and ecological regeneration.

Such a shift isn’t just theoretical; it has practical implications.

For instance, implementing circular economy approaches could transform industries from fashion and FMCG sectors to agriculture and digital technologies. Not only making them more sustainable to operate within planetary boundaries, but also creating new opportunities for innovation and even meaningful employment. A step closer to “co-founding a type 1 civilisation” as I express in the poem, bringing into being a civilisation that harmonises with, rather than exploits its surroundings.

Element Prompt: WaterHow would your life and your community change if well-being and ecological regeneration were the primary economic indicators? What steps can you take to move from a linear to a circular mindset in your own consumption and lifestyle choices?

Creating waves of radicle change

In a world marked by escalating challenges, radicle change is not just an aspirational call-to-action. It’s an imperative for human and biospheric survival. My poem serves to emphasise this call-to-action, beckoning each of us to step up and act as designers and architects of our own collective destiny. It’s a challenge to all of us to re-evaluate the stories we tell, the memes we share, and most critically, the shared values and actions that give shape to our existence on this beautiful planet.

To engage in the kind of radicle change we’re talking about, it’s crucial to understand that we are dealing with systems – interconnected, complex, and often highly resistant to change.

The field of complexity science offers us valuable insights here. It introduces us to concepts like attractor states which are more stable configurations within a system that “attract” the . These states can sometimes be disrupted by small yet impactful interactions, offering us opportunities for systemic change. Likewise the idea of emergent properties demonstrates how the whole can be greater – and significantly different – than the sum of its parts. These aren’t just academic points; they provide us with a prism of lenses to identify leverage in systems.

At Tethix we’ve incorporated these concepts into our vision of the ETHOS platform. A network of ETHOS instances, Archipelagos and Gardens. A vision that is not just about technological infrastructure but a living ecosystem enabling collective problem-solving through bottom up emergence and participatory ethics. While traditional models rely on a centralised and top-down imposition of ethical frameworks, ETHOS aims to cultivate transdisciplinary collaboration that taps into the wisdom of the crowd. In essence, we’re not just shifting the pieces within the existing paradigms, we’re evolving the game board itself, guided by a moral compass that is collectively tuned and re-tuned as we navigate the complexities of our time. I’ll note here that we think big and build tiny, and our first version we are soon to launch in a pilot is a simple Slack app. Humble beginnings.

The problem we have fallen in love with (the ethical intent to action gap) requires us to move away from the isolated genius model toward a more collective form of problem-solving. We wholeheartedly recognise that the challenges we face are so multifaceted that no single institution, organisation or sector can tackle them alone.

Collective intelligence and coopetition

At first glance, nature seems like an arena where the survival of the fittest reigns, with organisms locked in an eternal struggle for limited resources. But take a deeper dive – à la Alice in her quest for understanding – and we find a more nuanced picture. Beneath the veneer of competition lies a deeply interconnected web of symbiotic relationships and mutualisms. Take mycorrhizal fungi and trees, for instance. The fungi obtain sugars from the trees and in return, help the trees absorb water and minerals. It’s a win-win situation in a world that seems bent on zero-sum games.

In complexity science, this pattern – where individual, selfish actions inadvertently result in beneficial collective outcomes – is known as an emergent property. It suggests that cooperation isn’t just a touchy-feely ideal but a critical evolutionary strategy. This is exemplified in theories like Robert Axelrod’s “The Evolution of Cooperation,” where mathematical models like the Iterated Prisoner’s Dilemma demonstrate how cooperative strategies can emerge even in competitive settings.

But how can we harness this inherent drive for “coopetition” for societal problem-solving? This is where collective intelligence comes into play. Think of a Wikipedia model but for complex socio-technical issues – a decentralised platform where individual contributions, guided by a dynamic framework of shared values and goals, contribute to a well-rounded understanding of challenges. The underlying mechanisms of collective intelligence mirror the “Wisdom of Crowds” theory, popularised by James Surowiecki. According to Surowiecki, diverse, independent individuals often make more accurate collective judgments than even the smartest single member in the group. But note: the key is diversity and independence. Without those, we risk groupthink or echo chambers.

Element Prompt: WaterSo, imagine you’re Alice, exploring not just a library but the immense database of human experience and wisdom. What if you could tap into this collective know-how, transcending geographical and ideological barriers, to generate solutions that are greater than the sum of their parts?

Moral imagination and systemic change

Visionary change is often seen as the byproduct of grand ideas and revolutionary movements, but its roots are sometimes more humble than we might imagine. Martha Nussbaum, a philosopher who has keenly explored the concept of moral imagination, argues that such sweeping changes often start as a flicker in the individual mind. This flicker isn’t just intellectual – it’s deeply emotional, having connections between cognitive empathy and ethical reasoning.

In this interconnected digital age, we’re inundated with decisions that have ethical weight. From how we engage in social media debates to how we design and build technologies that impact society at large. Ethical frameworks like utilitarianism or deontology provide somewhat of a foundation for these decisions. Putting aside that most people wouldn’t want to dive into these areas of philosophy. But what they lack is this deeper human element that moral imagination can bring to the table.

Imagine for instance if AI (or insert the term SALAMI as Timnit Gebru prefers) were designed not merely to optimise algorithms but also to consider the full spectrum of human values and experiences? A much richer tapestry in our nature than we can possibly account for in SALAMI systems at present (if ever). This is where moral imagination comes into play. And it’s uniquely human. A machine can’t empathise, have compassion or feel. Moral imagination goes beyond mere mathematical or rule-based optimisation to ask deeper questions about the lived experience of people, communities and our precepts of fairness, justice or the longer-term impact of our decisions on other people and the planet we all live on.

The power of stories and actions

So, what became of Alice in Wilderland? We imagine that she was inspired by her reading, adventures in Wilderland and her intrinsic sense of existential hope, and enrolled her grandfather, parents, friends, teachers and fellow students in shaping a rainbow mirrored vision for a community and place based project. She and her network of radicles found common alliances and created a collective intelligence platform drawing from the principles she learned about mycelium networks. She initiated a resource-sharing program that connected her neighbourhood like never before. Her community became a microcosm of cooperation, resilience, and ingenuity, offering a glimmer of what humanity could achieve when our collective moral imagination is harnessed.

The power of our stories lay in their ability to ignite the flame of possibility. Our collective challenges, though monumental, are not insurmountable. By pooling our collective intelligence and moral imagination, we can turn the tide. We can become, as I express in the poem, ‘cultural tsunamis in this sea,’ surging forth at a horizon with existential hope and towards the lands of human and planetary flourishing.

Element Prompt: WaterImagine you are Alice uncovering insights from the book on the Wisdom of Wilderland. What experience, ideas, or concepts have ever made you feel hopeful about the world’s complexity and the challenges we face as a species? How did it change your perspective on what’s possible?

Thanks to my friend and colleague Alja for bringing life to this post with the cover imagery.

If you want inspiration for the radicle change we need, you can learn from the billions of years of R&D and immerse your senses sitting in the garden or going for a walk in the park if you can without listening to that latest podcast. Attune to the wisdom all around you.

Even if when you can’t there’s a fantastic website from the Biomimicry Institute Ask Nature