We are techne-optimists.

But wait! Don’t throw that tomato.

We are not fanpeeps of the a…………….z Techno-Optimist Manifesto. Our unique flavour of ‘techne-optimism’ (something we will later describe, largely due to our value system, assessment of ‘the facts’, and our philosophy of technology, as something like the bio-psycho-social-cultural-economic-techne belief that things can get better, potentially much better, if we more deeply connect, authentically and inclusively collaborate, and effectively coordinate wise and responsible relational action… Fuck! We’ve just given it away) has been core to the living philosophy of Tethix prior to day 1.

The goal of this essay is to:

- Set a decent scene: Explore the general idea of techno-optimism, how might one relate to the idea (including its limitations / problems), and how might one work through a formal process to assess whether one is in fact a techno-optimist (or something like it, as we allude to above). We will also clarify the shift away from ‘techno’ to ‘tékhnē’

- Explore the unhealthy concoction that is the Techno-Optimist Manifesto: Need we say more? And

- Describe how we might better work together to increase the probability of preferable futures: Think of this a beautifully ambitious, shared, yet genuinely pluralistic vision for how we might live in healthy relation to one another, and life itself, in the future.

We expect this – a genuinely preferable future – will include (and of course, not be limited to) a wise, responsible and ecological relation to technology.

As a basic proxy, you might liken this preferable future to Glen Albrecht’s symbioscene, a possible epoch where humanity, the technologies we design (and that in turn – given what Daniel Fraga has recently referred to as ontological design – design us) and the rest of the ‘natural world’ (yes, that preposterous fucking notion that the natural world is something ‘out there’ that is separate from us…) exist in balance. Such a world requires us to find ways beyond systemic ecological overshoot and rampant inequality and inequity. It requires us to progress beyond multipolar traps, our obsession with infinite growth and myriad perverse incentives. It requires us to move beyond arms races of all kinds. It requires us to first imagine, then act together, to biodegrade that which is unhelpful, while collectively crafting that which can meaningfully carry us forward, the seeds and saplings that might eventually become a thriving ecology for millennia to come.

Increasing the probability of such a preferable future – whatever form that takes, which will not be driven by some top down homogeneous mandate, but rather some type of dynamic dance between the macro, meso and micro scales – likely requires us to embody relationality, love and an action oriented existential hopefulness.

Alright. Basic setup done.

Take a deep breath in, hold for a brief moment, slowly and purposefully release… Give thanks to the brilliance of your parasympathetic nervous system.

Ready? Let’s do it.

Part 1: Positioning our techne-optimism

In ‘Techno-optimism: an Analysis, an Evaluation and a Modest Defence’, Danaher presents readers with an ‘Argument template for techno-optimism’. It goes:

(1) If (a) the good probably does or probably will prevail over the bad and (b) if technology probably plays a key role in ensuring this, then techno-optimism is the correct stance.

(2) The probable current and/or future facts are F1…Fn [Facts Premise]

(3) The agreed upon value criteria for determining whether the good prevails over the bad are V1…Vn [Value Premise]

(4) The good probably prevails over the bad, given F1…Fn evaluated in light of V1…Vn [Evaluation Premise]

(5) Technology probably plays a key role in ensuring that (4) is true (Technology Premise].

(6) Therefore, techno-optimism is the correct stance.

We use this as basic inspiration for our work below. But before moving, let’s clarify what might already be obvious. We refer to techne-optimism, rather than techno-optimism. In ancient Greek philosophy, tékhnē is a concept that refers to making or doing, and is modernly thought of as relating to practical knowledge. Because of our underlying metaphysics, value system and broader relational philosophy, this framing makes a heck of a lot more sense.

Our working definition of Tékhnē is the skillful art and craft of relationally applying knowledge, moral imagination and wisdom to reveal ‘reality’ through embodied praxis. Doing so based on the belief that such a collective and relational endeavour increases the likelihood of tomorrow being better than today is where optimism comes in (we discuss how this comes into tension with traditional views of optimism below).

Defining our value system

A brief digression… One way to explore Metaphysics is through areas of philosophy that relate to it (and are sometimes thought of as existing ‘within’ it), namely ontology (what exists), epistemology (what can be known, how we can know it etc.), axiology (what we value and why) and cosmology (our story of the universe, the meaning we derive from this etc.). We aren’t going to dive deep into this ‘field’ in the essay you’re reading. We are working with too many practical constraints, and the reality is that such an endeavour is like an infinite unfurling of doorways through wilderland.

What does need to be clearly stated – the explicit point of this digression – is that nothing that human’s describe (or perhaps experience for that matter) is metaphysically agnostic. Everything is imbued with assumptions about what exists and what can be known. These assumptions massively impact our capacity to sense-make. They frame how we relate to ideas. They’re implicated in, and give rise to, our very sense of life itself.

To better understand what we really mean by the claim, “nothing that human’s describe is metaphysically agnostic”, allow us to introduce Philosopher of Science, Bjørn Ekeberg. In this interview on the ‘shaky foundations of cosmology’, Dr Ekeberg describes some of the challenges facing the Standard Cosmological Model. He highlights the very nature that, even within the ‘natural sciences’ (the ‘hard’ sciences if you will), there are powerful metaphysical assumptions all over the place*. You might find the Einstein example particularly useful.

*This is not to say that science is not incredibly useful, powerful and illuminating. It most certainly has been, can be and will continue to be. It is to suggest that science, like all human constructs, has limitations, is driven by assumptions and is grounded in narrative.

It’s pretty darn rare to talk about metaphysics or our deep underlying assumptions and beliefs. But just because it’s uncommon, doesn’t mean it’s not important. So, here we are.

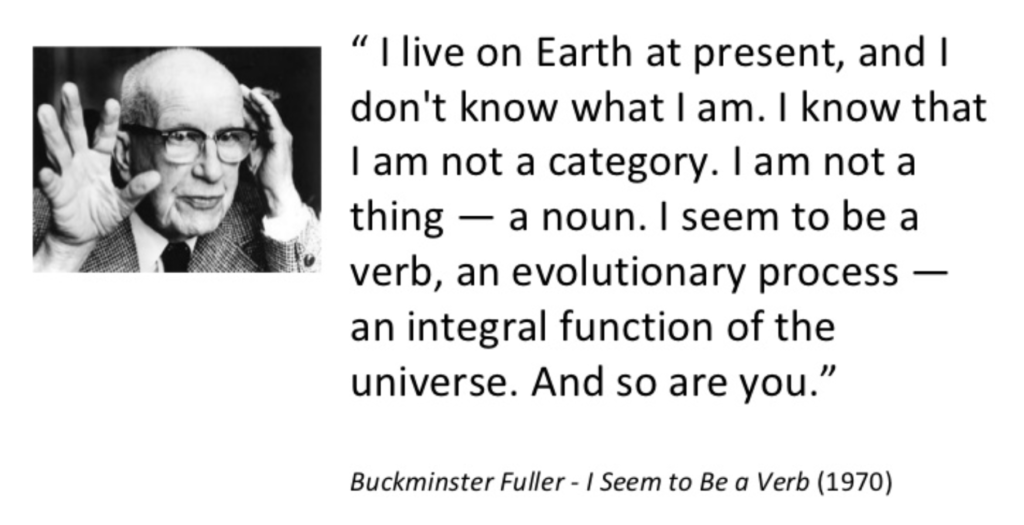

We ‘know’ we operate in relation to metaphysical beliefs. We hold them fairly lightly. We try to make them as explicit as we can, but it’s likely many remain implicit. We can’t always grasp them with the limitations of language. With that said, Bucky does a decent job here:

With our digression done, defining a basic value system feels like the most useful place to go next. This impacts everything we do and think of as a team. It’s expressed through a dynamic dance of what we think exists, what we think we can know and our interpretation of the story of the universe.

To start with, let’s make a normative claim (something we believe ought to be done because it’s good and right): Humanity should actively work together to create a world where every person on this planet lives a healthy and dignified life, within biophysical limits (the ‘safe operating zone’ in relation to Earth System Boundaries).

You can think of this as our core value premise.

Within this, of course, there’s nuance. We can’t possibly cover the entire field of value theory, or the ways in which we relate to it. Nor can we really describe everything that we value or we think we ought to value in some type of linear, dot point list (we’re not even sure that’d be helpful).

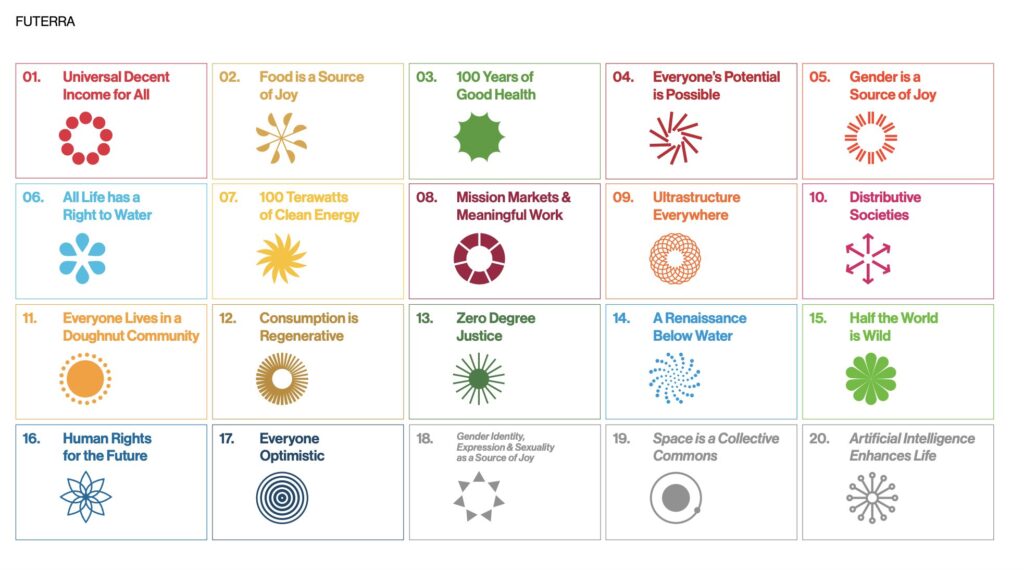

Instead, imagine there was some type of guiding value like the above. Now also imagine something like the below, taken from Futerra’s Awesome Anthropocene Goals, as the basic guiding framework that supports more specific action across the macro, meso and micro scales of connection, collaboration and coordination (something we describe in our response to the Australian Government’s Draft Science and Research Priorities).

This is the basic substance of what we value. It’s not an exhaustive description of course, but it should usefully support the rest of this essay.

The facts (past, present, projected, possible and preferable)

Now, this section really is worthy of an entire library of books. I mean, how can you get at something like this usefully given the spectrum of interpretations, limitations of empirical evidence and about a million other ‘variables’? In short, you can’t. Instead, let’s focus on something like a brief and directionally useful approximation.

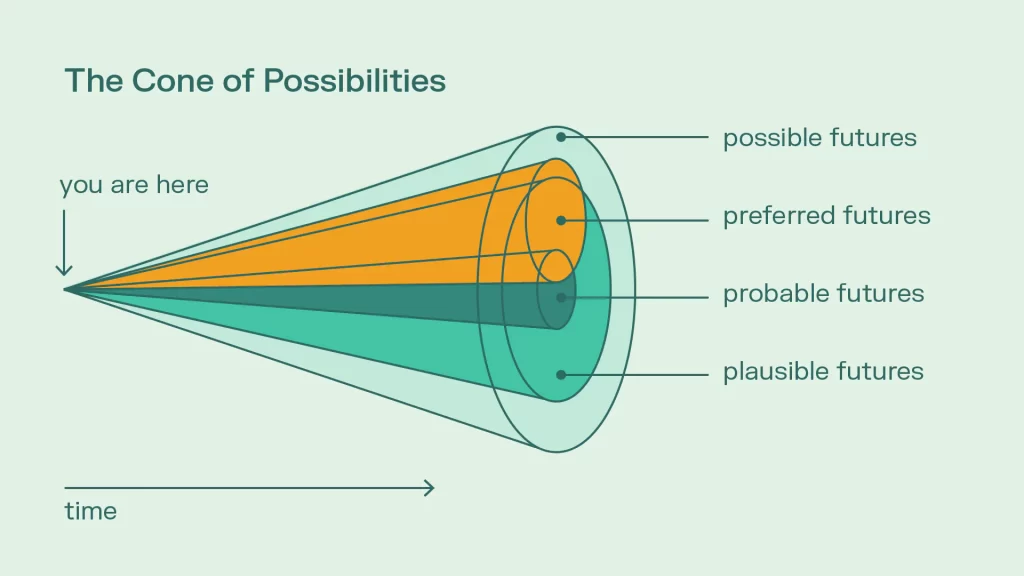

To do this we will use The Futures Cone. This is a visual tool used in futures studies to represent the possible, plausible, probable, and preferable futures emanating from the present moment (we also like to go back to try and make sense of how the present moment came to be).

We use this to draw attention to futures that we might collectively agree are good and better, so that we can actively engage in the living process of moving closer towards them.

The past

Homo sapiens are approximately 300,000 years old. And although we’ve experienced a heck of a lot during that time, the reality is that very little can be truly known about how things have played out.

Sometimes the stories we are told about ‘our history’ suggest that there have been fairly clean transitions. The idea of the agricultural revolution is one such example. However, as Wengrow and Graeber have suggested, it seems as though a ‘closer to truth’ telling might be far more colourful and experimental. For instance, the idea that, combined with different forms of social organising, agriculture was something different cultures or communities ‘tried’. Some continued. Others ‘chose’ to stop. Others were more dynamic, residing in one fairly stable place for part of the year, therefore relying at least in large part on some form of agriculture, yet during other times of the year were far more nomadic and dynamic, relying on something more like foraging and hunting (different social organising structures came with each ‘mode’).

All of this is to suggest, as we alluded to in the opening of this section, we can’t really do justice to the longer-term history of our species in this essay. So, let’s explore a little of the last 500 or so years, which aligns to the emergence of capitalism and its organising principles, along with the big impacts of what we now generally think of as modern technology, our political economy and a genuinely interconnected and interdependent global civilisation.

To start with, a story, perhaps one that was bubbling away in certain ways for a couple of thousands years, became deeply entrenched. It, the ‘modern story of separation’, goes something like:

- Nature is a machine (and more broadly, the universe is inanimate)

- Humans are separate from nature

- Humans are separate from each other

- Human progress arises from the conquest of nature

- The Earth is a resource to exploit for human benefit

- The purpose of life is to be wealthy and powerful

Former Lord High Chancellor of Great Britain, Francis Bacon, suggested that us walking, talking apes, “… “render ourselves the masters and possessors of nature” and “… “establish and extend the power of dominion of the human race itself over the universe”.

Fark.

It’s pretty heavy stuff.

We can then argue, in conjunction with the rise of capitalism (approximately 500 years ago), the discovery of fossil fuels (enabling our energy obsession), new forms of education, scaling the mechanisation of ‘work’ and plenty of other stuff in between (some wonderful and some fucking terrible), that this vision came true on a planetary scale (going universal was probably a wee bit ambitious. Fermi anyone?).

We are without a doubt highly intelligent. But, as we look back, embody what is here now and consider what might come next, we have to ask, are we really living in loving relation to the process of wisdom seeking?

The present

As we write this, there are multiple wars being waged. Some are obvious and overt, others are far more subtle and hidden away. Half the planet is on fire (Taylor Swift literally just cancelled a concert in Rio. This is impacting EVERYONE). The other half is treading water (close to literally!). People are sad and depressed. We socialise less, have less sex and seem far less hopeful about the future. The cost of living is skyrocketing. The wealth divide is more extreme than it’s ever measurably been. We don’t seem to trust institutions, arguably for justifiable reasons. This is non-exhaustive, but you get the picture.

As usual, The Juice get at this ‘enshittenment’ powerfully. And for a less satirical take, here’s Wellbeing Economy Alliance and Greenpeace on ‘what do we mean when we say change the system’.

Yet when looking at certain quantitative data points, which always need to be interrogated with care and humility, life has never been better than this for such a huge group of people. Infant mortality is way down. We’ve all but eradicated certain diseases. We have access to all the material ‘stuff’ the heart – well, since the invention of PR/Propaganda anyways – could ever desire. Our technologies afford us certain privileges that are beyond the wildest imaginations of those living mere generations ago. We can eat blueberries, even when they’re out of season! Oh those antioxidants, the explosion of flavour, the overdone but always classic ‘blue tongue lizard joke’… Maybe just an Aussie thing?

Anyways, the story is nuanced. Our world is terrible. It’s also bloody brilliant. And maybe, just maybe, it can be far better.

But, and the next section will further animate this, those who professionally study civilisational collapse seem to broadly agree that the civilisation we know and are actively a part of today is in the process of collapsing. Whether this is net good or net bad is beyond the scope of this essay.

Projected futures

Alright, let’s start strong. We are amidst the Sixth Mass Extinction (basically defined as a series of events and circumstances that leads to the permanent loss of greater than 75% of all life forms). This has been referred to as “mutilating the tree of life” thanks to the fact that current extinction rates are 35 times higher than expected background rates.

Next little nugget.

Worst-case climate projections have underestimated current warming and extreme events. This is a whole can of worms of course, that needs to be situated within the context of transgressing at least 6 of the 9 planetary boundaries and the fact that the latest paper by Hansen et al. finds that we will exceed 1.5 degrees celsius in the 2020s, and 2 degrees before 2050. Our response will require unprecedented levels of global coordination, full economic decarbonization and perhaps solar geoengineering to return to Holocene-like temperatures.

Honestly, do we have to go on from here? I mean, we had a pretty darn good picture of this back in 71’ when the Club of Rome funded Limits to Growth. If you want more on the last 50 years or so of that story, here you go. And none of this really gets into the technosphere, war or any of the other problems (genuine existential risks) that arise from the seemingly huge gap between our power and wisdom (obviously not all existential risks stem from this, unless someone is somehow magically manipulating super volcanoes, solar flares and other cosmological goodies).

With all of this and sooooooooo much more as the backdrop, it’s hard to know whether we are more likely to come together or further divide.

Going from possible to preferable

Although there’s a lot to all of this (how many bloody caveats can we fit into one essay…?), one significant problem (in addition to entrenched inequality, power imbalances, unhealthy stories about separateness etc.) is our imagination. With all this bad news in our projected future, it’s hard to see the light at the end of a very deep, dark tunnel. It’s hard to imagine going from possible to preferable. It’s hard to direct our transitionary efforts towards a world that feels far too utopic.

Interestingly, recent neuroscience research into the Default Mode Network (DMN) offers some timely insight. The more vividly we can imagine an event, the more detailed and influential our construction of potential futures becomes.

This is huge. And we don’t mean in the manifest / ‘the secret’ kind of way.

Similar research also suggests that the emotional weight we assign to imagined future events influences our evaluation and prioritisation. In essence, positive emotional valence can lead to a greater desire to achieve a particular future, whereas negative valence may serve as a warning or deterrent (this is why Rainbow Mirrors are sooooo important).

In summary, all the ‘black mirror’ stuff in literature, entertainment and other media is deeply wired. This leads us to inter-subjectively believe that the ‘bad’ is more probable. It’s something like a self fulfilling prophecy.

Today we seem to be so entangled in the ‘business-as-usual’ mindset. This keeps many of us tethered to the familiar, while inhibiting our ability to imagine radically different futures. This shared mental model constraint narrows the possibility space, reducing our capacity to purposefully and planet positively innovate.

But, all hope is not lost amigos. By adopting what we might call a “collective futurecrafting” approach, we can leverage social cognition to encourage a more vivid and detailed envisioning of diverse futures.

Remember what we wrote earlier: “It requires us to first imagine, then act together, to biodegrade that which is unhelpful, while collectively crafting that which can meaningfully carry us forward, the seeds and saplings that might eventually become a thriving ecology for millennia to come.”

As we engage in this collective envisioning, we are effectively participating in a synaptic remapping process. By repeatedly imagining varied and preferable futures, we can rewire our brain’s (and bodies) to be more receptive to the types of changes we together broadly agree are ‘good’ and ‘right’.

This is, to put it bluntly, one of the biggest challenges and opportunities we have ever faced.

How we think about technology

As with every other section, this is worth many doctorates. We draw inspiration from folks like Heidegger, Latour and Haraway, who arguably have quite uncommon or non-traditional (more all encompassing) views about technology’s nature.

Our views are of course not limited to those three thinkers. We also draw inspiration from indigenous knowledge and indigenous knowledge systems (sometimes thought of as Traditional Ecological Knowledge or ‘TEK’ in this context, essentially the collective body of knowledge about ecological relationships and the ways in which this is held, shared, learned and applied. In Australia, first nations peoples have Songlines, a way for storing knowledge in memory by adapting song, art, and most importantly, Country, into peoples lives. Close to home for Nate and Mat, Abdilla, Poelina, Yunkaporta and Kelleher, and many other first nations people’s work has influenced how we attempt to relate to Country, which of course impacts our work in sociotechnology ethics), varying philosophical traditions outside the typical western purview (Ubuntu, Buddhist, Confucian, Taoist, phenomenology of aidagara i.e. “betweenness” etc.), postmodernist perspectives such as Gilligan’s work on care, and many other sources (such as ‘nature’ itself).

As a brief introduction, we will suggest that (noting, of course, this has metaphysical flavouring to it. Told ya we’d make some of this explicit!):

- Humans are not just part of nature, we are nature. In fact, we cannot actually be separated from it, now matter how hard we try.

- The technologies we design are a reflection and extension (not just augmentation) of us.

- The technologies we design have various feedback loops that in turn massively impact who we are, how we relate to one another and how we exist together in this life.

- The technologies we design are not abstractions, but can be thought of as being ‘real’, in something like the way we are. They are made from fairly similar building blocks. As a result, they massively impact biospheric systems (due to their material flows and everything that follows). One could go so far as to suggest that technology is also nature.

- If the universe is relational, and we exist not as ‘things’ but as some kind of ‘process’, then technology is a part of that living process. It has been for hundreds of thousands of years in varying forms.

Our philosophy of technology can therefore be thought of as one of deep entanglement; us to ‘it’, it to us, us and it to Gaia (noting of course, we are all Gaia) to us to it… You get the picture.

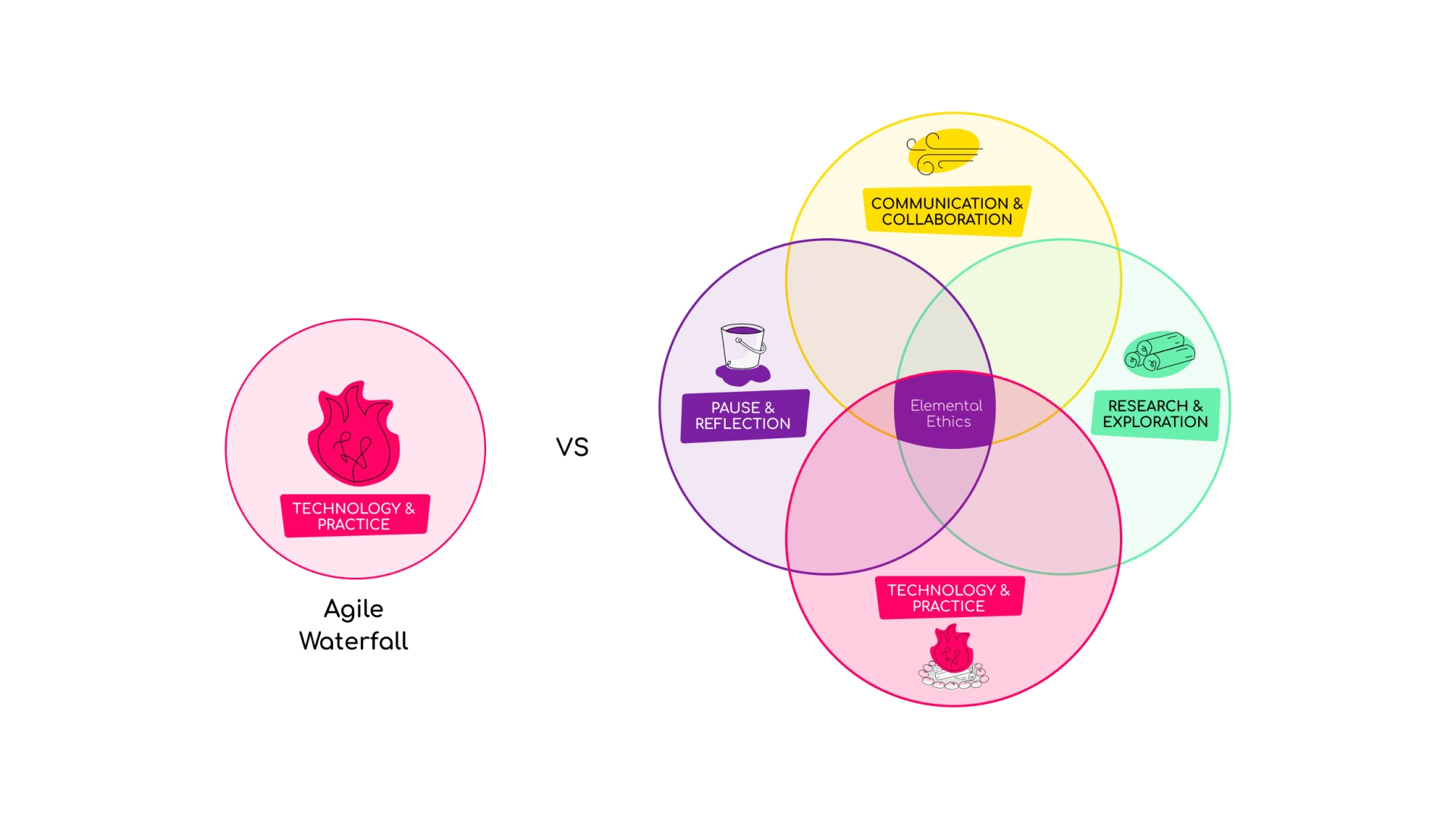

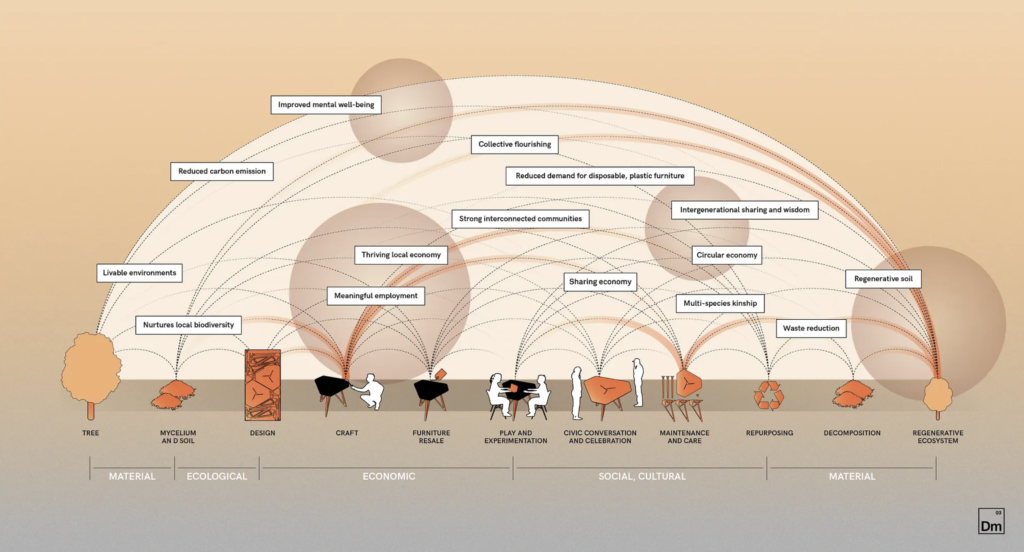

Indy Johar and the Dark Matter Labs team write beautifully about similar perspectives here. The images above, from that article, are hopefully a useful 2 dimensional approximation for what we’re trying to get at.

This, as with all we discuss in this essay, is a taste at most. Regardless, we hope it begins animating some of our positioning, mostly in service of showing how it seems to radically differ from our friends in Menlo Park.

Evaluating ‘net good’

Given our view of the past, present and possible futures, and considering our briefly summarised philosophy of technology, let’s discuss why we feel something like a bio-psycho-social-cultural-economic-techne optimism is a useful model.

Think of this as the belief that, overall, things can get better. We believe this can result from wise and deliberate effort, based on a much larger ‘circumference of care’, a significant shift in how we relate, and the incredible power of deep connection, purposeful collaboration and effective coordination across macro, meso and micro scales.

It’s worth noting here that this comes into tension with traditional ideas about optimism. We are not saying things will be good or better. We are saying they can be good or better.

This is due to the fact that we, first and foremost, do not know. We cannot know. This is where that epistemic humility comes into play. But it’s also because of our facts premise. The trajectory that the preponderance of empirical evidence suggests we are on is scary AF. It suggests life, due to planetary instability (and potentially many other factors), is likely to get much worse if we continue with anything close to business as usual.

Therefore, our specific flavour of bio-psycho-social-cultural-economic-techne optimism is based on the belief that we have the capacity to radically transform how we relate to one another and life itself. Through this process we can support one another through some of the greatest challenges we have ever faced, and perhaps, just perhaps, come out the other side in better shape than ever before.

The idea of a useful model is really a way to describe an orientation that actually makes sense, that might directly contribute to making things better.

Unfounded beliefs about magical technology and free markets won’t help, mostly because it encourages us to double down on so much shit that isn’t working. Yet completely throwing the baby out with the bathwater (getting rid of ‘technology’, or hardcore authoritarian regulation, or whatever other flavour this might take) might be equally unwise.

We need to dance with complexity and avoid the dogma.

Onto the evaluation. Drumroll…

Guess what? We can’t evaluate based on Danaher’s framework. Why? Because that framework and its framing defines technology as something that is separate from us, just like ‘nature’ in the modern story of separation.

Instead, what we can say (broken record alert!) is that we believe in the possibility of better. We believe in our collective capacity to ‘transcend the paradigm’, biodegrade the harmful, bridge divides and support one another through the difficulty, destruction and despair. To do this we must actively exist in relation. Our relationality, deep care, love, and action oriented existential hopefulness is the recipe for different conditions that give rise to new and more ‘positive’ forms of emergence. All of this is our way to a better world.

Summary

As you can see from this brief tour of our adapted argument for techno-optimism, we are describing ourselves as some, albeit fairly unique, flavour of techne-optimists. This is based on (TL;DR summary):

- Our value system

- Our assessment of ‘the facts’

- Our speculations about possible futures

- The ways in which wiser, more responsible technology design, deployment and use (an inherently relational, non-dual process) can contribute to making preferable futures more probable. And

- Our belief in humanity’s collective capacity to causally influence said preferable futures by leaning into the challenges and working together to explore ways to progress beyond

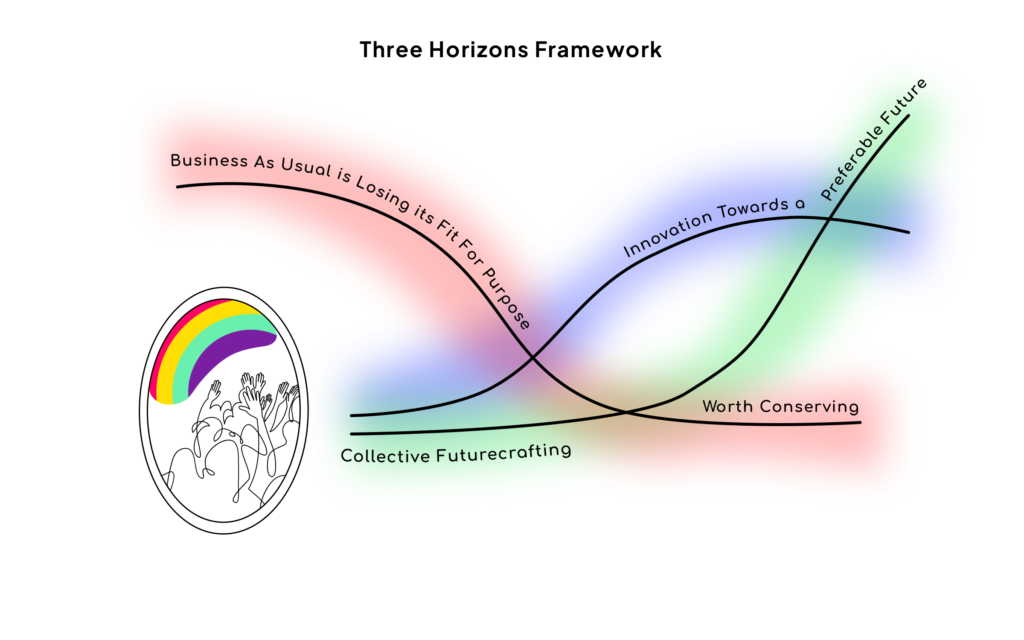

Before getting into some of the more useful stuff around the Three Horizons Framework, we do need to say a thing (or many!) about our accelerationist friends over at a16z and beyond. Due to practical constraints, we cannot systematically analyse every ‘belief based’ statement that features in the manifesto. What we can do is call your attention to some concerning – based on our value system, assessment of ‘the facts’, expectations about what is both possible and preferable, our philosophy of technology and a few other bits and bobs – ‘themes’ that prominently feature in the text.

Prior to that, we will call your attention to the 2022 paper published in the Annual Review of Environment and Resources, ‘Digitalisation and the Anthropocene’. In this paper, Creutzig et al. highlight the fact that “digitalization has historically increased environmental impacts at local and planetary scales, affecting labor markets, resource use, governance, and power relationships”. When combined with the latest review of decoupling in The Lancet, which demonstrates that sufficient absolute decoupling is happening way too slow (that’s the gist anyways), it seems very hard to justify the strong techno-optimist view of (certain types of) technology and ‘free markets’ saving us from ecological overshoot* and the myriad issues that relate to and depend on it (if your strategy is a fancy ass bunker, then a rocket to some micro colony on mars… well, we can see how your views may differ from ours).

*We build upon this in the theme about biophysical (il)literacy.

Theme 1: Elitism and a fundamentally distorted worldview

The manifesto oversimplifies complex socio-economic issues, attributing them almost solely to a lack of technological advancement (and enabling the freedom of free markets to operate of course). It’s a reductionist narrative that feels elitist, assuming a one-size-fits-all technological solution, whilst overlooking systemic inequalities that are well established empirically.

Mat took it up himself to watch this episode of The Ben and Marc show, where the two founders of a16z discussed the Techno-Optimist Manifesto. There seems to be a serious lack of reflexivity (this is specifically present as they discuss certain types of powerful personas, but don’t seem to realise they are amongst the most elite / powerful / influential people in the world), amongst many other things.

To Ben and Marc’s credit, there’s some attempted mythopoetic sense-making and a few other things that feel more nuanced than the manifesto itself.

Theme 2: Misquoting and half-truths

The quotations and historical narratives within the manifesto are not the result of an integrous sense-making process, but rather an attempt to reinforce a dogma that has already been established. Such a narrow and selective representation distorts our understanding of technological development and its wide spectrum of impacts, from the most wonderful to the utterly woeful.

Theme 3: Tech as a panacea

Positing technology as a solution to all material problems in this context feels like a strange kind of naive progress narrative, an indulgent form of technological determinism. The entire manifesto overlooks the nuanced relationality of technology, society, and the rest of the biosphere.

Nate Hagens addressed the point about 1000x-ing (well, Marc actually wants to see something like a 5000x increase from where we are today) energy usage recently. As Nate highlights, the perspective in the manifesto is ‘catastrophically energy blind… well intentioned, but absolutely clueless of the physics, the energy and the ecology of our situation’. To cuddle this one home, the waste heat alone (and this is assuming low-carbon/renewable sources), would increase global average temperatures by 40 degrees fahrenheit (about 4.5 degrees celsius). Not long after this the oceans would literally boil…!!! Happy days eh?

Theme 4: The Free Market as god (in other words, worshipping Moloch and amplifying the metacrisis)

This endorsement of free markets oversimplifies the complex dynamics of market economies and overlooks market failures and the mother of all elephants, externalities. The content also seems to assume a level playing field, which is utter BS. Whether we look at the Gini Coefficient or other methods of assessing inequality, the story is the same. Inequality is getting worse, not better. Most of (not all, of course) the benefits of modernisation go to the few, in the form of capital accumulation.

Yada yada.

Adding to this, Herman Daly, one of the most prominent figures in ecological economics and former Senior Advisor to the World Bank, once said “Economics is an ideology masquerading as a science.”

Also, this reddit thread on ‘When Idiot Savants Do Climate Economics’ is enjoyable and insightful. It also relates to Theme 7.

It might be time to start taking aspects of economics as something less than ground truth people.

Theme 5: Historical and philosophical dirt

What can we say here… The manifesto demonstrates an unfounded and poorly grounded understanding of historical and philosophical contexts. It articulates something like a linear view of progress, which misses viewpoints that acknowledge the complex, typically non-linear, interactions between technology, humanity, culture, our environment and society.

We don’t get the sense that the a16z crew live in loving relation to the process of wisdom seeking (if you’re looking for philosophy, you won’t find it in the manifesto).

Theme 6: Reinforcing the SV mindset

This is a promotion of techno-utopianism (it feels strangely like some of the early episodes of Silicon Valley where a certain billionaire builds a mechanical island… Then dies!) that lacks critical engagement with the broader socio-political and ethical implications of technology development. And there will be no ‘negotiation with the enemy’ (tech ethicists).

Theme 7: Biophysical incompatibility

Briefly, “the term ‘biophysical’ describes the abiotic and biotic conditions of an environment and includes chemical, biological, physical and ecological components. These conditions and processes can occur naturally (e.g, currents), and/or be influenced by anthropogenic drivers (e.g., ocean warming).”

You may have noticed (putting it kindly) ‘insufficient’ detail in the manifesto (again, 1000x-ing energy as the claim, with zero substance to back it up). There was nothing substantive about earth system sciences or any other field that attempts to deeply understand, using the best tools we have, the impact of humanity’s activities on biospheric systems (and how all of that impacts the short, mid and long-term liveability of this planet).

Given the very strong belief based statements about what technology (SV magic that a small few ‘control’) might enable us to do, we would have expected more. We would have expected consideration for the years of inquiry since Limits to Growth was first published. We would have expected an articulation of how said magic would somehow overcome the Jevon’s paradox. We would have expected some substantive information about how sufficient absolute decoupling might be achieved.

But no. Just no. All ideology, close to no science and certainly no actual philosophy. It is a manifesto after all.

Let’s call this section here. We could go on, and hope we do through more dynamic and deliberate discussion. But for now, you have almost certainly gotten the gist.

Pathfinding together towards better horizons

Here’s Kate Raworth introducing you to the Three Horizons Framework.

If you’re not familiar with this, please stop reading and watch the video. It really is one of the best explanations, including practical examples, of the framework out there.

So what can we say here that’s useful?

Firstly, let’s talk about H1. Think of this as BAU. We all know a shit load of what we now consider BAU has to stop. So let’s suggest that we need to come together to explore how we can practically and relatively safely ‘biodegrade’ the stuff we’re currently doing that is harmful.

Let us now introduce you to H3, the preferable future.

This is where we work to establish a beautifully ambitious vision about how we’d love to live together, in healthy relation to the rest of life on this planet, in the future.

This isn’t some utopia where we ride unicorns. Although, sign us up if that’s on the cards. Rather, it’s something like a collective remembering and returning. A reconnection to the sacredness of life (read: something we ought to regard with great respect, just because). Here we spend our days living healthy, dignified, creative and thoughtful lives, as best we can. And we find ways to do so whilst only taking from the world what can be regenerated in the same time period (living within planetary boundaries).

Importantly in this context, we see this as resulting from wise relation to both ‘low’ and very ‘high’ tech.

Now we have to talk about getting there. As we discussed earlier, there’s no one path to rule them all. But, we do need to ensure that our path is supporting the vision (H2+) and not reinforcing the status quo (H2-). This will require us to caringly connect, courageously collaborate and consciously coordinate our actions.

This does not have to mean sameness or homogeneity. But rather a broad vision about certain goals and boundaries, then plenty of flexibility to express our agency, creativity and cultural preferences.

It’s our belief that we can do this. Seriously. Humanity at it’s best is absolutely fucking beautiful.

It’s time to give ourselves the chance to be just that.

If any of this resonates, come pathfind with us.

Sending love to you and beyond, always.

I’d like to thank my colleagues Mat and Alja for the way we balance the elements in our work together. Special thanks also to Adrian Hindes for reviewing and commenting on this work.